BEGINNINGS: THE PATTERNS OF SUCCESS

24 WHO ACHIEVED IT TELL HOW THEY GOT STARTED

BEGINNINGS: THE PATTERNS OF SUCCESS

24 WHO ACHIEVED IT TELL HOW THEY GOT STARTED

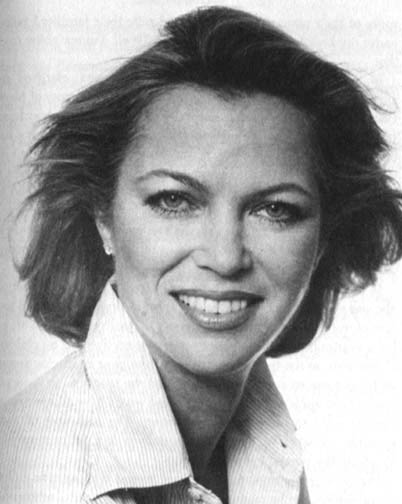

Louise Fletcher, who was born in Birmingham, Alabama, and studied drama at the University of North Carolina, began her professional career as a television actress in California. After an eleven-year break she returned to acting with a minor role in the film Thieves Like Us, which she accepted more or less as a favor to director Robert Altman. Due to the critical acclaim the film received, she decided to return to a full-time career. She attributes part of the reason for that decision to the women's movement, which encouraged her to feel she could pursue acting while also being a wife and mother. It took more than a year, however, before she was able to find an agent who would represent her. Her second film earned her an Academy Award as Best Actress of the Year for the role of Nurse Ratched in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.

I was in the most trouble I've ever been in in my life the day I went to the movies by myself for the first time. I was eleven, and the picture was Lady in the Dark with Ginger Rogers. It had a tremendous impact on me, and I sat through it again and again from the time the theater opened at one o'clock in the afternoon until it closed that night. When I got home I found out my parents had the police out. They were really scared.

I was in the most trouble I've ever been in in my life the day I went to the movies by myself for the first time. I was eleven, and the picture was Lady in the Dark with Ginger Rogers. It had a tremendous impact on me, and I sat through it again and again from the time the theater opened at one o'clock in the afternoon until it closed that night. When I got home I found out my parents had the police out. They were really scared.

The picture had put me in a trance. I never noticed when it started or ended, and it sparked something in me -- the thought that I could aspire or dream to be something else, somebody different. It was a portrait of a woman who was one thing -- very cold and businesslike -- but she had a secret life. In her dreams she was something else. It made me feel that if I put my mind to it I could change the pattern of my life, and I wanted very badly to change it. I wanted a life different from what other girls my age were planning. Southern girls thought the thing to do was what their mothers did: grow up, get married, have children, and stay at home. It was a life without surprises, and I didn't want that. I knew I was not going to do that -- that I was going to do something else.

My parents were ambitious for us. They were both totally deaf, and they kept telling us -- my brother, my two younger sisters, and me -- that we had all the advantages, all our faculties, and that we could become whatever we wanted to be. I believed them. I bought it, and I still believe people can do whatever they really want to do.

I had minor skirmishes with wanting to be a doctor. I wanted to be a concert pianist. I wanted to be a professional tennis player. Mostly pushy, showy things -- but they were more fantasies than real ambitions. From the time I was very young, maybe five or six, I thought a lot about being an actress. I didn't tell my friends about my ambitions, though, especially when I got older, because I thought they would not receive them well. I never talked about what I wanted to do. It was like my secret life, and when my friends spoke of their plans to get married and raise their families I talked under my breath. I would say to myself, "Well, I'm not going to do that."

In high school I became very active in drama, clarified my ambitions, and went on to major in drama at the University of North Carolina. Acting came fairly naturally to me. Dinnertime at home was a complete show. To explain to our parents what the day had been like, we would act it out. It was, "Guess what happened to me today? I was sitting on the bus, and this old lady was sitting next to me, and..." And you would be the old lady, and you would be yourself. We did that every night. I got a lot from my mother too. Even though she's extremely shy, she's an incredible mimic and can imitate anybody physically. She'd walk the way other people walked and get terrific laughs.

It was my Aunt Beezie who really started my interest in acting. She was a flamboyant character. She lived in Bryan, Texas and took care of us four kids at different intervals in our lives. I lived with her for a year once and visited her every summer. She had no children of her own, so she treated us like dolls. She gave us singing lessons and piano lessons and dressed us up, and she taught us to show off. She and my uncle were very sociable and would have a lot of people over at night to play cards or whatever. The high spot of those evenings was when we kids got dressed up to do a skit or something to amuse the guests. I loved it.

My father was a minister, and, since several of us went to college at the same time, he couldn't pay for us all. So I had a scholarship from the Episcopal Diocese of Alabama. Twice a year I had to go and see the bishop to report on how I was doing at school and to get my check for the next semester. He was an incredibly handsome, six-foot five-inch man with a great shock of white hair. He had been a wrestler at college and was enormous. He was what I imagined God to be, and after our talks -- when I got up to say good-bye -- he would put his arms around me. It was like God embracing me, and he would say in his deep, vibrant voice, "Remember who you are and what you represent." I thought I was the only person he ever said that to, until I visited his grave in Alabama in 1976. There on his stone was Remember who you are and what you represent. He said it to everybody. But he had the ability of making you feel you were the only person in the whole world he even thought of saying it to, and I've never forgotten it.

The day I graduated in 1957 I left for California with two roommates from college. One of them had a car, and the trip was my graduation present -- my expenses and a couple of hundred dollars. I really would rather have gone to New York, since all my training had been in theater, but I didn't have the guts to go there alone. I knew only one person in New York, and that was a man. What I needed was a woman. That's the way Southern girls thought. So I went to California because I had two girl friends to go with. It was easier. My interest in acting was overwhelming, but I wasn't thinking, "I'm going to California and I'm going to become a movie star." Things were different then. I lived just for the moment, and whatever happened, happened. Somewhere in the back of my mind, though, was the ambition to get to New York.

I had very lucky breaks in the beginning. Looking back, I know I made them happen by seeking out certain things. When we arrived in California I started going to acting classes and got a job during the day as a receptionist for a pediatrician in Beverly Hills. One day Lee Phillips, who had just been a big smash in the movie version of Peyton Place, came in with his kids, and I asked him, "What are you doing now?" He said, "I'm doing a Playhouse 90 on CBS." I thought, "Oh my God. Such a dream." It must have showed on my face, because he asked if I would like to be an extra in it. "I'd love it," I told him.

The next day he called and told me to be at CBS at a certain time to meet John Frankenheimer, who was directing the show. Besides giving me the job, when he heard I didn't have an agent Frankenheimer called MCA, and they gave me an appointment as a favor to him. I did a scene in their basement theater from something I was working on in acting class, and they signed me. They began submitting me for roles, and I started to work pretty steadily in television. I quit my job in the doctor's office, and as interest grew I began to get bigger and better parts.

Live television drama was like live theater, because you moved without thinking about the camera. It followed you around. In film you have to be more aware of what the camera is doing. One of the first shows I did on film, rather than on videotape or live, was an Alfred Hitchcock presentation. The director, Norman Lloyd, said, "Well, you know all about film." I said, "Sure." I played Barry Sullivan's secretary and had a scene where I came into his office, heard a gunshot, screamed, turned, and ran out. After the master shot they changed the setup for a closeup on Barry Sullivan, but I didn't notice they had rearranged the camera, lights, and everything. Norman Lloyd said, "Okay. Do the same thing as you did before." So I came into the office, there was the gunshot, and I screamed, turned, and ran out -- knocking down lights, flags, people. I was so embarrassed and humiliated that I could feel the heat in my face, and I kept going. I ran into my dressing room and started to cry. Barry Sullivan came in and said, "What do you care what they think? They don't have to scream and run. Don't be embarrassed." I made it a point after that to check out where everything was. You learn awfully fast when you go through an experience like that.

One of my first starring roles was in The Lawman series with John Russell. That was about 1960. It was quite a showy piece, and based on it Warner Brothers offered me a seven-year contract, which I turned down. They were furious and so were my agents, but I felt it was the right thing to do. It was supposed to be for television and film, but Warner Brothers was doing little but television in those days. To me it just seemed they wanted an actress to run from one show to another. It all boiled down to cheap labor. They wanted to pay me $700 a week, instead of the $1,000 I had been getting, for however many weeks a year were involved. Some people argued that the studio would have given me a lot of publicity and that I would have gotten a break in a movie, but the movies they were making then were on the order of Ice Palace.

I kept working in television, and then I tested for the picture Where the Boys Are and got the part. That was going to be my big break. Before the film started I got married and went on a honeymoon to Mexico City. While we were away Paula Prentiss appeared from out of a cloud. She was sort of zany, and they preferred her personality to mine. I was not zany -- which is not to put her down at all, for she was perfect for the part -- and when I got back from the honeymoon they had given the part to her. I was terribly discouraged but kept working until 1962 when, on my last job, I was five months pregnant. After our son Andrew was born I wasn't interested in television anymore. It wasn't that rewarding, and I didn't work for the next eleven years.

When we married, my husband -- Jerry Bick -- was a literary agent, but he sold his business in 1966 because he wanted to become a film producer. The next year we moved to England, where he had a film to do, and we stayed there for six years. While we were there he kept saying, "All these English actresses are playing American women on the screen. It's ridiculous. You ought to do it." But I had totally given up the idea of acting. Once in awhile I'd see a film with a really good part and think, "Oh, boy, I could do that," but I would forget it by the time I left the theater.

About 1971 Jerry was working on a film Robert Altman was to direct -- Thieves Like Us -- and Altman said he wanted me to play one of the parts. I joked about it. "You've got to be kidding," I told him. "Not only am I not going to do it, but it's an insult for you to think of me as that woman. She's fifty at least." It was an important film for Jerry, and that was another reason I didn't want to be in it. I didn't want the responsibility. Plus, I was the producer's wife, with all that means. There were just too many things going against it, in addition to the fact that I really wasn't interested. The movie finally got off the ground two years after Altman first offered me the role. We wound up on location in Mississippi, and they still hadn't cast the part. Altman said to me, "You're going to do it." I said, "No, I'm not," but when it came time to shoot they still were counting on me. So I said, "Okay. I'll do it."

I should have been scared after being away from acting for so long, but I was preoccupied with a lot of other things. I was a housewife taking care of two sons. I had reverted to type. I also knew I could handle the part. It was a Southern woman aching for a respectability she never was going to get, and I had known so many people like that. Altman was a big help too. He was marvelous. Once he casts you, you feel there's nobody else who can do the part the way you can. He has the gift of making you feel you're unique for it. Because of the kind of role it was, I could look awful. I didn't have to look good, and looking good can be a big worry. There was not the hassle of getting made up -- going through the Hollywood routine of two hours with people poking at your face and your hair so that by the time you get to the actual shooting you're terrified. I just got out of bed in the morning, went to work, and played the part.

Thieves Like Us was not a big money-maker but it was a critical success, and it was a major turning point for me. When I saw it I thought, "That's not bad. I can do that again." I felt very positive and decided that when we got back to California I'd return to work. But it wasn't so easy to do. It took me more than a year to get an agent. I didn't want to draw on any favors, so I contacted only those agents I didn't know. Their responses were incredible: "Why do you want to work? Your husband makes a good living." "I have a lot of middle-aged women who can't get work." Awful things like that.

During the eleven-year period when I had psyched myself up to be a mother and a housewife, I tended not to be able to do two things at once. After Thieves Like Us, though, I came to believe that I could work and do those other things at the same time. It was difficult, but the women's movement had had a big effect on me -- not in any sort of active way, because I wasn't carrying placards or anything, but the articles I read and the interviews I heard had a definite effect on me. I came to accept that it would be okay for me to do something for myself. In fact, during the time I was looking for an agent it was the period of Watergate, and that inspired me to consider trying something really different. I felt I wanted to help change things, and I was thinking, "Why are you doing this to yourself? You're not too old to go to law school."

Finally I went to see an agent I had had at MCA, Wally Hiller. He was very kind and took me on as a favor. It was just coincidental that a week later I got my first interview for Cuckoo's Nest. Milos Forman, the director, had seen Thieves Like Us and called me. The first interview was just a casual meeting with Milos. We talked for an hour about Europe, about what I had been doing, about mutual friends. It was very pleasant, and I left. The next meeting was with the producer, Michael Douglas, and the executive producer, Saul Zaentz. It was another sitting-around-talking meeting. Then I got a call to see Milos again and read for him. At this point I was feeling, "Jesus. They're really interested," but I also was hearing all sorts of rumors, such as that Lee Grant had already gotten the part. When I met with Milos we read through a few scenes together. Afterward he said, "Take these two scenes. Learn them and come back at five o'clock."

I had two or three hours, and when I got back Michael and Saul were there too. They obviously weren't convinced and wanted to see me do it. I did the scenes, with Milos playing all the parts except mine. We would do it one way, and -- probably to see if I could take direction -- he'd say, "No. Let's try it this way." When I got home that evening I thought, "Oh, God. I was terrible. Just terrible." It was December 1975. Jerry had a film to do in Vancouver, and we left for Canada the next day. We were there about two weeks when, the day after Christmas, the phone rang. It was Wally Hiller. He said, "What's a nice lady like you doing playing an awful nurse like that?" I threw the phone down and ran screaming through the apartment. My kids thought I had lost my mind. When I came back and picked the phone up I asked, "How much do they want?" We started filming on January 4 in Oregon.

I feel really, really lucky to have had the eleven-year break away from acting -- not to have had more success in those early days. Hollywood can keep you from growing up, and being an actress allows you to be immature if you want to be -- especially in dealing with other people. I saw myself in 1977 in a television repeat of a Perry Mason show I did in the early days. I was a cute little thing with big eyes and still had a trace of a Southern accent, but there was nothing there. I was like something that hadn't been finished. I wasn't even a person. The years of living abroad and growing up in other ways -- not in the Hollywood world -- helped.

We all have potentials in us that we don't develop. I'm sure I have potentials in me now that are not developed; that I could and should be developing. People tell me that I've arrived, but I don't feel that way. Maybe it's just that you always want to keep doing things better and better.

Copyright 1978 Thomas Y. Crowell Publishers.